Join Us Live for a Discussion on Medicare, Democracy, and the Future of Health Care

Medicare Financing: Shifting the Focus to Sustainability in Addition to Solvency

- Positions and Publications

This Medicare Sustainability series is produced by the Medicare Rights Center, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to ensuring access to affordable health care for older adults and people with disabilities. Since 1989, Medicare Rights has provided direct counseling, educational resources, and policy advocacy to help people navigate Medicare and to strengthen the program for current and future beneficiaries.

When it comes to Medicare financing, public discussion often starts and ends with the trust funds becoming “insolvent.”[i] But that is not the whole picture. As we explain below, solvency—the ability for Medicare to pay for care—is not at risk for the majority of Medicare. Part A does have solvency risk because of a series of arbitrary funding decisions.

But that does not mean Medicare sustainability is unimportant. Ensuring Medicare is a robust program for the millions of people it serves must be a focus for policymakers, with a critical eye toward limiting overspending and promoting affordability.

Medicare’s Funding Structure

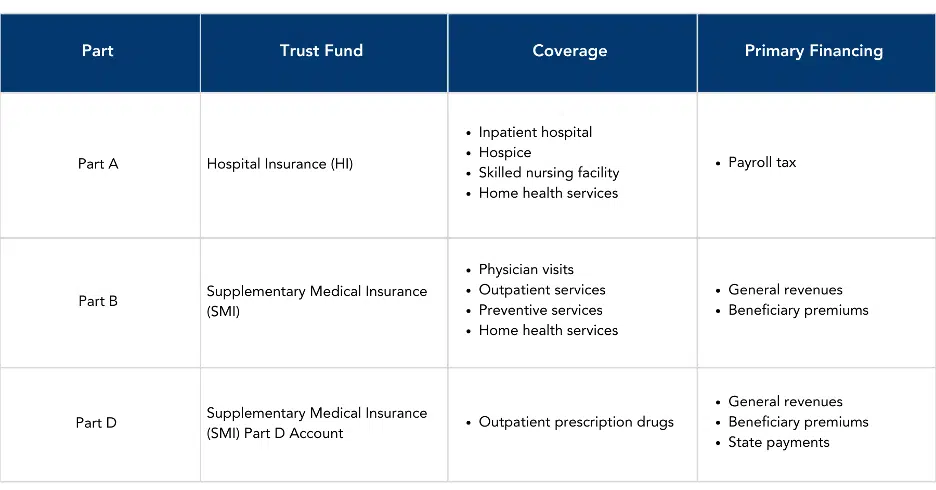

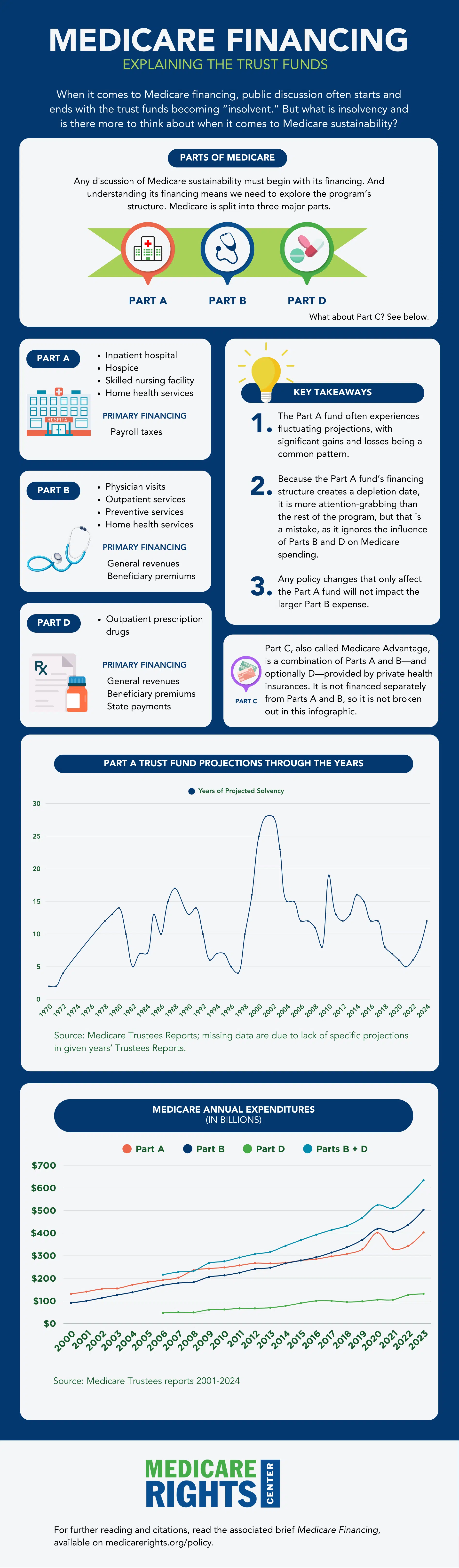

Any discussion of Medicare sustainability must begin with its financing. And understanding its financing means we need to explore the program’s structure. Original Medicare is split into three major parts.[ii]

As the chart shows, the different Parts have separate funding mechanisms. The majority of Medicare is funded through general revenues and beneficiary premiums; only the Part A Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund is funded through payroll taxes.[iii] Because the HI fund is so tied to payrolls, it varies with the state of the economy. High employment and expanding payrolls mean more money in the HI fund; as unemployment rises or payrolls contract, fewer dollars flow to the fund. The HI Trust fund’s current inability to tap into general revenue means it lacks the flexibility of the rest of Medicare to weather economic downturns.

By contrast, the SMI Trust Fund, which covers spending for physician and outpatient services, is funded through general revenue. This means that it can continue to pay even in an economic downturn.

How We Got Here

The Social Security Act of 1935

Social Security was created through the Social Security Act, which was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 14, 1935.[iv] The new program provided benefits to retirees based on their earnings history, financed through a dedicated payroll tax.

Some lawmakers criticized this financing as “regressive”[v]—a type of tax that is more burdensome to low-income earners than high-income earners.[vi] Part of that is by design: When the law was passed, only the first $3,000 of payroll income was subject to tax. This tax base was increased several times in the ensuing decades, reaching $6,600 in 1965, the year Medicare became law.[vii]

The Social Security Amendments of 1965

The bill that created Medicare Part A and Part B was signed into law on July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon Johnson.[viii] The road to passage was lengthy, and often contentious. One key debate centered on how the benefits should be funded.

Lawmakers agreed that Part B should be voluntary and funded through general revenues, but Part A funding was a different matter. On one side were lawmakers who wanted participation in Part A to be compulsory, with benefits funded through a payroll tax like an extension of Social Security. On the other side were lawmakers who thought Part A enrollment should be voluntary, like Part B, and funded through a combination of premiums—with some arguing for sliding scales based on income—and general revenues.[ix]

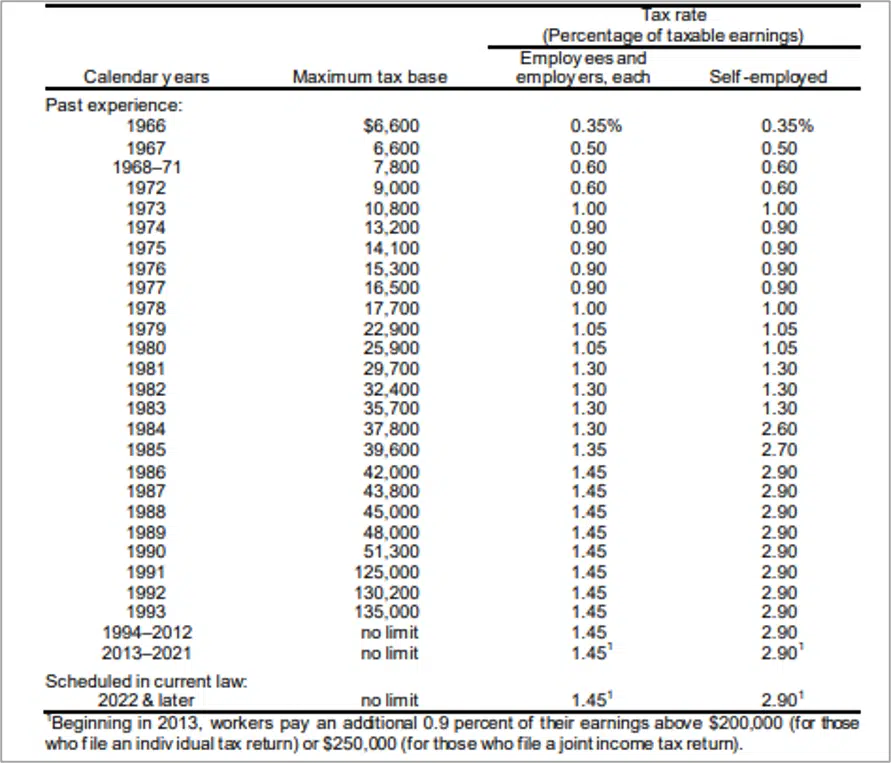

As with Social Security financing, the prospect of Medicare financing using payroll taxes was met with objections because of its regressive structure.[x] Many also argued that it was perplexing to have one funding mechanism for Part A and another for Part B.[xi] Congress did eventually opt for the payroll tax. The rate was set at 0.35% with scheduled increases for future years and shared Social Security’s income cap ($6,600).[xii] The legislative history shows that Congress assumed future legislators would continue to adjust the Social Security cap or the HI tax rate as appropriate.[xiii]

Increases to the Income Cap

Not long after establishing Medicare, Congress again bumped up the income amount subject to the Social Security and the new HI taxes. The first increases were statutorily set at specific levels: From $6,600 to $7,800 in 1968,[xiv] then to $9,000 in 1972.[xv] Then came two decades of alternating between such prescriptive increases and automatically adjusted caps.[xvi]

In 1990, when the cap was $51,300,[xvii] Congress made a radical change and decoupled the HI tax base from Social Security’s cap. They set the new HI tax base at $125,000 for 1991, and at $130,200 and $135,000 for 1992 and 1993 respectively[xviii] to “improve the progressivity of the tax system… [and] provide necessary funding for the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and… enhance its long-term solvency.”[xix] Soon after, in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, Congress completely eliminated the cap on earnings subject to the HI tax.[xx] This means all earned income is subject to the HI tax; in contrast, the Social Security cap is still in place at $168,600 for 2024.[xxi]

Increases to the Tax Rate

For the tax rate, the 1965 statute included built-in increases until 1987, when they would top out at 0.80%.[xxii]

But Congress quickly abandoned this schedule and began a series of increases to the tax rate in 1968 that eventually reached the current rate of 1.45% in 1986.[xxiii]

In 2010, passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)[xxiv] added another payroll tax to the mix. The “Additional Medicare Tax” is a 0.9% tax on high earners’ wages. This tax pays for some ACA provisions in Medicare and also funds other provisions like the premium tax credit.[xxv]

The Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)

The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 amended the ACA and added the NIIT, a 3.8% tax on investment income for households with modified adjusted gross income over $200,000 for individuals and $250,000 for couples.[xxvi] Confusingly, though it was created under the heading of “Unearned income Medicare contribution,” the text of the statute does not designate the funds to go toward the HI trust fund, or to Medicare generally.[xxvii]

Trustees Reports Projections

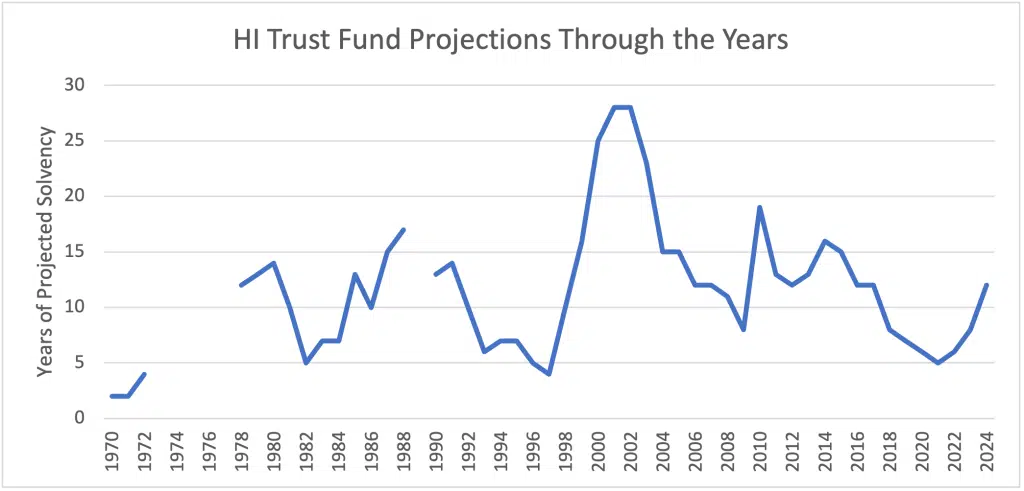

The annual Medicare Trustees Report discusses the financial status of both the HI and SMI trust funds, and projects the HI fund’s depletion date. (As discussed above, because it is funded through general revenue, the SMI fund does not have a depletion date.) The HI exhaustion date is based on fluctuating amounts of revenues collected and benefits paid, along with predictions about future revenues and spending.[xxviii] As these balances shift, so do the trust fund’s assets. Importantly, even at depletion, the fund would remain operational, with revenues from payrolls continuing to flow in and benefits continuing to be paid out, albeit at a reduced percentage.[xxix]

In 2023, the Medicare Trustees estimated a depletion date of 2031. In 2024, they extended it to 2036[xxx] at which time the HI fund would be able to pay an estimated 89% of claims.[xxxi]

Fluctuating projections, with big gains and big losses, are a common pattern for the HI fund. For example, from 1980 through 1982, the projections went from 14 years to 10, then to 5. In another block of years, 1997’s projection was only 4 years, climbing year by year to peak at 28 years in 2001.[xxxii]

When the projected depletion dates cause enough consternation, they can trigger congressional intervention, like the statutory changes described above. Historically, each sharp dip in the depletion dates led to a corresponding congressional action—such as changes to provider payments—and a subsequent rise.[xxxiii]

What about the SMI Fund?

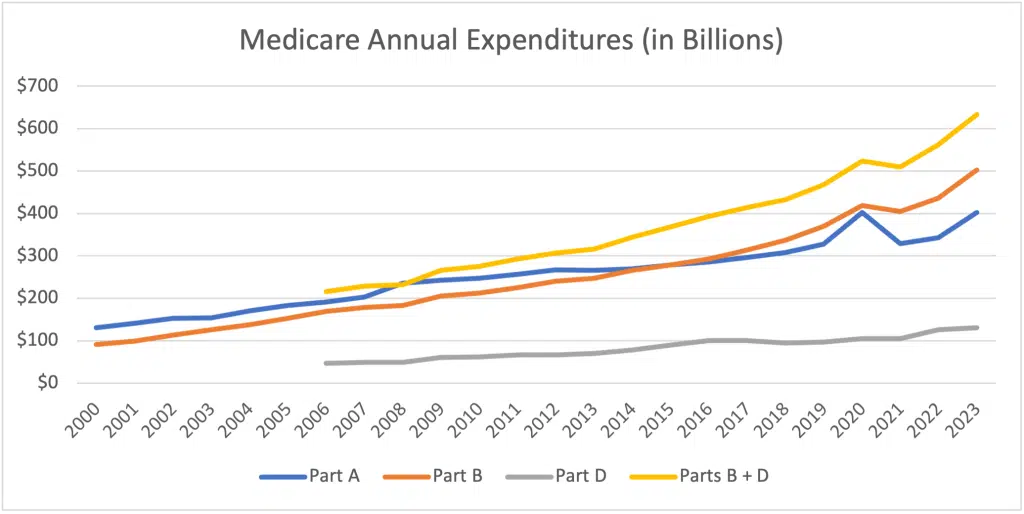

Because the HI fund’s financing structure creates a depletion date, it is more attention-grabbing than the rest of the program, but that is a mistake, as it ignores the influence of Part B on Medicare spending. Since 2016, Part B spending has outstripped Part A spending, and the combined draws on the SMI fund far outpace the HI fund.

Any policy moves that only address the HI fund would have no impact on this larger SMI expense. And excluding the SMI Trust Fund from conversations about Medicare sustainability leaves taxpayers and beneficiaries on the hook for increased Part B spending.

Discussion

As shown above, the amount of funding flowing into the HI trust fund is a policy choice that was historically subject to change to fit new circumstances. The rate for most taxpayers has been stagnant since 1986 despite significant growth in medical spending since that time. The 2024 Trustees report estimated that increasing the HI tax by 0.35% would alleviate projected solvency issues for the HI fund and extend the depletion date past the 75-year window of their analysis.[xxxiv] Redirecting the NIIT into the trust fund where it was intended to go would also reduce solvency concerns.

These and other analyses show that Medicare’s structure and funding do not have to be written in stone. Focusing solely on the HI trust fund creates an inaccurate perception of both where Medicare spends most of its funding and what steps could be taken to alleviate funding pressures.

Historical fluctuations in the Trustees projected depletion date, and the congressional intervention to delay it, demonstrate an important point: “Since the inception of Medicare in 1966, the HI trust fund has always faced a projected shortfall.”[xxxv] This is not an accident. As Dr. Marilyn Moon—a former Public Trustee of the Medicare and Social Security Trust Funds—explains, “The Part A Trust Fund and its projections were essentially put into place to offer an early warning sign for the need for funds to assure that Medicare would continue to function without interruption. It is not a signal of the need for cutting back on services.”[xxxvi]

As the bulk of Medicare’s expenses shift from the HI fund to SMI, a trend experts anticipate will continue,[xxxvii] hyperfocus on the HI fund will only further disguise opportunities for meaningful cost savings.

And reforms are needed. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 was a significant step in reducing future drug costs, especially in Part D. The Congressional Budget Office initially projected that the three key drug provisions—price negotiations, inflation rebates, and the Part D redesign—would reduce Medicare spending and the federal deficit by $129 billion from 2022 through 2031.[xxxviii] This is a significant improvement, though subsequent CBO calculations show that Part D subsidies to avoid premium shocks have eaten into those savings.[xxxix]

There is still more to be done, both in drug pricing and in other reforms. Medicare Advantage overpayment alone,[xl] caused by a mixture of inadequate benchmarks, favorable selection, bonus payments, and upcoding, wastes billions per year,[xli] and is projected to waste hundreds of billions or even more than 1 trillion dollars over the next decade.[xlii] Tackling this overpayment, alongside establishing site neutrality across Medicare, should be priorities for creating a more sustainable Medicare future.

Tackling all segments of Medicare, in ways that center beneficiary needs and preferences, will be necessary to improve the sustainability, affordability and, yes, solvency of the program for future generations.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. Medicare Rights Center maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis and communications activities.

Endnotes

[i] See, e.g., Zachary B Wolf, “Medicare and Social Security insolvency is right around the corner” (February 9, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/09/politics/medicare-social-security-what-matters/index.html; Chris Farrell, “Medicare Could Be Insolvent In 2024: How To Prevent It” (March 5, 2021), https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2021/03/05/medicare-could-be-insolvent-in-2024-how-to-prevent-it/?sh=2785eca726f0.

[ii] Part C or Medicare Advantage is a combination of Parts A and B—and optionally D—and is not separately financed.

[iii] Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, “2024 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds” (May 6, 2024), https://www.cms.gov/oact/tr/2024; Juliette Cubanski & Tricia Neuman, “FAQs on Medicare Financing and Trust Fund Solvency” (May 29, 2024), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/faqs-on-medicare-financing-and-trust-fund-solvency/.

[iv] Pub. L. 74-271.

[v] Geoffrey Kollmann & Carmen Solomon-Fears, “Major Decisions in the House and Senate on Social Security: 1935-2000,” Congressional Research Service (March 26, 2001), https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/crsleghist3.html.

[vi] Julia Kagan, “Regressive Tax: Definition and Types of Taxes That Are Regressive” (February 6, 2024), https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/regressivetax.asp.

[vii] Kevin Whitman & Dave Shoffner, “The Evolution of Social Security’s Taxable Maximum: Policy Brief No. 2011-02” (September 2011), https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/policybriefs/pb2011-02.html.

[viii] Pub. L. 89-97.

[ix] Geoffrey Kollmann & Carmen Solomon-Fears, “Major Decisions in the House and Senate on Social Security: 1935-2000,” Congressional Research Service (March 26, 2001), https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/crsleghist3.html.

[x] Geoffrey Kollmann & Carmen Solomon-Fears, “Major Decisions in the House and Senate on Social Security: 1935-2000,” Congressional Research Service (March 26, 2001), https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/crsleghist3.html.

[xi] See, e.g. Congressional Record, “HOUSE 7353” (April 8, 1965), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1965-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1965-pt6-2-1.pdf (“It is difficult for me to understand the wisdom of financing some medical care through social security taxes and the rest through voluntary insurance systems.” Odin Langen (R-MN)).

[xii] Wilbur J Cohen & Robert M Ball, “Social Security Amendments of 1965: Summary and Legislative History,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 9 (September 1965), https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v28n9/v28n9p3.pdf.

[xiii] Wilbur J Cohen & Robert M Ball, “Social Security Amendments of 1965: Summary and Legislative History,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 9 (September 1965), https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v28n9/v28n9p3.pdf.

[xiv] Pub. L. 90-248.

[xv] Pub. L. 92-5.

[xvi] Pub. L. 92-336; Pub. L. 93-233; Pub. L. 95-216.

[xvii] Tax Policy Center, “Historical Social Security Tax Rates, 1937 to 2022 [1]” (February 11, 2022) https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/statistics/pdf/ssrate_historical_2.pdf.

[xviii] Pub. L. 101-508.

[xix] “House Report 101-881 for H.R. 5835” (October 15, 1990), https://www.taxnotes.com/research/federal/legislative-documents/public-laws-and-legislative-history/omnibus-budget-reconciliation-act-of-1990-p.l-101-508-title/dsm4.

[xx] Pub. L. 103-66.

[xxi] Social Security Administration “How is Social Security financed?” (last visited September 30, 2024), https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/HowAreSocialSecurity.htm.

[xxii] Wilbur J Cohen & Robert M Ball, “Social Security Amendments of 1965: Summary and Legislative History,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 9 (September 1965), https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v28n9/v28n9p3.pdf.

[xxiii] Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, “2023 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds” (August 31, 2021), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-medicare-trustees-report.pdf.

[xxiv] Pub. L. 111-148.

[xxv] Internal Revenue Service, “Topic no. 560, Additional Medicare tax” (last visited June 10, 2024), https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc560;. Andrew M Slavitt, “Letter to Senator Ron Wyden” (January 10, 2017) https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CMS%20Medicare%20solvency%20letter%20Final%20Signed.pdf.

[xxvi] Public Law 111-152, §1402. Unearned income Medicare contribution.

[xxvii] 77 Fed. Reg. 72612 (“Amounts collected under section 1411 are not designated for the Medicare Trust Fund. The Joint Committee on Taxation in 2011 stated that “[i]n the case of an individual, estate, or trust an unearned income Medicare contribution tax is imposed. No provision is made for the transfer of the tax imposed by this provision from the General Fund of the United States Treasury to any Trust Fund.” See JCT 2011 Explanation, at 363; see also Joint Committee on Taxation, Description of the Social Security Tax Base (JCX-36-11) (June 21, 2011), at 24”); Leonard E. Burman, “ACA and the perils of reconciliation” (March 13, 2017), https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/aca-and-perils-reconciliation.

[xxviii] Gretchen Jacobson, et al., “Putting Medicare Solvency Projections into Perspective” (September 1, 2021), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2021/putting-medicare-solvency-projections-perspective.

[xxix] Juliette Cubanski, et al., “FAQs on Medicare Financing and Trust Fund Solvency” (June 17, 2022), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/faqs-on-medicare-financing-and-trust-fund-solvency/; The White House, “Fact Sheet: The President’s Budget: Extending Medicare Solvency by 25 Years or More, Strengthening Medicare, and Lowering Health Care Costs” (March 7, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/07/fact-sheet-the-presidents-budget-extending-medicare-solvency-by-25-years-or-more-strengthening-medicare-and-lowering-health-care-costs/.

[xxx] The Social Security Administration, “A Summary of the 2024 Annual Reports” (last visited June 10, 2024), https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TRSUM/.

[xxxi] Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, “2024 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds,” p 6 (May 6, 2024), https://www.cms.gov/oact/tr/2024#page=12.

[xxxii] Jim Hahn, “Medicare: Insolvency Projections” (updated October 25, 2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS20946.

[xxxiii] For a fuller picture of the relationship between statutory changes and the projections, see David Muhlestein, “The Coming Crisis For The Medicare Trust Fund” (December 15, 2020), https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/coming-crisis-medicare-trust-fund.

[xxxiv] Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, “2024 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds,” p 31 (May 6, 2024), https://www.cms.gov/oact/tr/2024#page=37.

[xxxv] Jim Hahn, “Medicare: Insolvency Projections” (Updated October 25, 2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS20946.

[xxxvi] Marilyn Moon, Testimony Submitted to The Senate Budget Committee, “Considering the Impacts on Beneficiaries in Medicare Financing” (September 27, 2023), https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/moon_test_927.pdf.

[xxxvii] KFF, “The Facts About Medicare Spending” (July 2024), https://www.kff.org/interactive/the-facts-about-medicare-spending/#share.

[xxxviii] Congressional Budget Office, “How CBO Estimated the Budgetary Impact of Key Prescription Drug Provisions in the 2022 Reconciliation Act” (February 17, 2023), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58850; Juliette Cubanski, et al., “Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act” (January 24, 2023), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/.

[xxxix] Congressional Budget Office, “Re: Developments in Medicare’s Prescription Drug Benefit” (October 2, 2024), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-10/Arrington_et_al_Letter_PartD_0.pdf.

[xl] Medicare Rights Center, “Medicare Advantage 101” (July 17, 2023), https://www.medicarerights.org/policy-series/medicare-advantage-101.

[xli] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “The Medicare Advantage Program: Status Report” (January 12, 2023), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/MedPAC-MA-status-report-Jan-2023.pdf; Richard Kronick, et al., “Industry-Wide and Sponsor-Specific Estimates of Medicare Advantage Coding Intensity” (November 17, 2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3959446.

[xlii] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “New Evidence Suggests Even Larger Medicare Advantage Overpayments” (July 17, 2023), https://www.crfb.org/blogs/new-evidence-suggests-even-larger-medicare-advantage-overpayments.

Recent Resources

Any changes to the Medicare program must aim for healthier people, better care, and smarter spending—not paying more for less. As policymakers debate the future of health care, we will provide our insights here.

Thinking ahead to Medicare's future, it’s important to modernize benefits and pursue changes that improve how people with Medicare navigate their coverage on a daily basis. Here are our evolving 30 policy goals for Medicare’s future.

You can help protect and strengthen Medicare by taking action on the important issues we are following, subscribe to newsletter alerts, or follow along on social media. Any way you choose to get involved is a contribution that we appreciate greatly.