Join Us Live for a Discussion on Medicare, Democracy, and the Future of Health Care

Medicare Site Neutrality: Pursuing a More Rational Payment System

- Positions and Publications

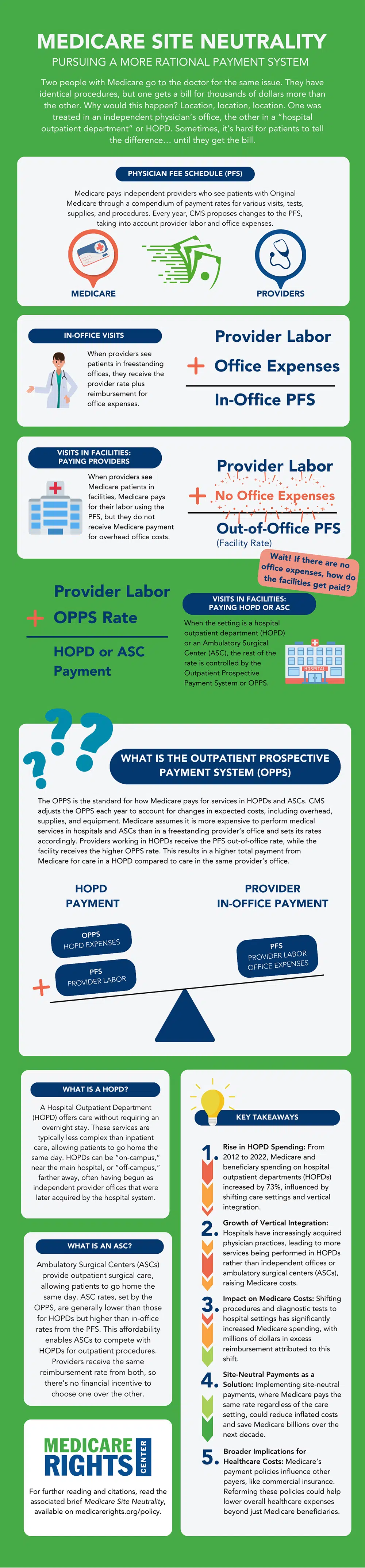

Two people with Medicare go to the doctor for the same issue. They have identical procedures, but one gets a bill for thousands of dollars more than the other. Why would this happen? Location, location, location. One was treated in an independent physician’s office, the other at a physician’s office that is owned by a hospital system and classified as a “hospital outpatient department” or HOPD.

When it comes to bills, this is a distinction with a big difference. Where a person gets their health care, in particular for Part B outpatient services, can be as important in the price as what care they get. Medicare typically pays HOPDs more than freestanding physicians’ offices,[i] even when the services are the same.[ii]

As explained below, payment differences like this create incentives for hospitals to buy up physician practices, ultimately shifting routine services to more expensive sites and driving up Medicare, taxpayer, and beneficiary spending.[iii]

How Providers are Paid

The Physician Fee Schedule

Medicare pays independent providers who see patients with Original Medicare through the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS),[iv] a compendium of payment rates for various visits, tests, supplies, and procedures.[v] Despite its name, the PFS covers other types of providers than just physicians. For example, the PFS is also used to determine how Medicare will pay nurse practitioners or marriage and family therapists.

Each year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposes additions, deletions, and adjustments to the PFS and finalizes it after receiving public comment. The list, and any changes, are intended to account for the labor of the provider, as well as overhead office costs like supplies and equipment.

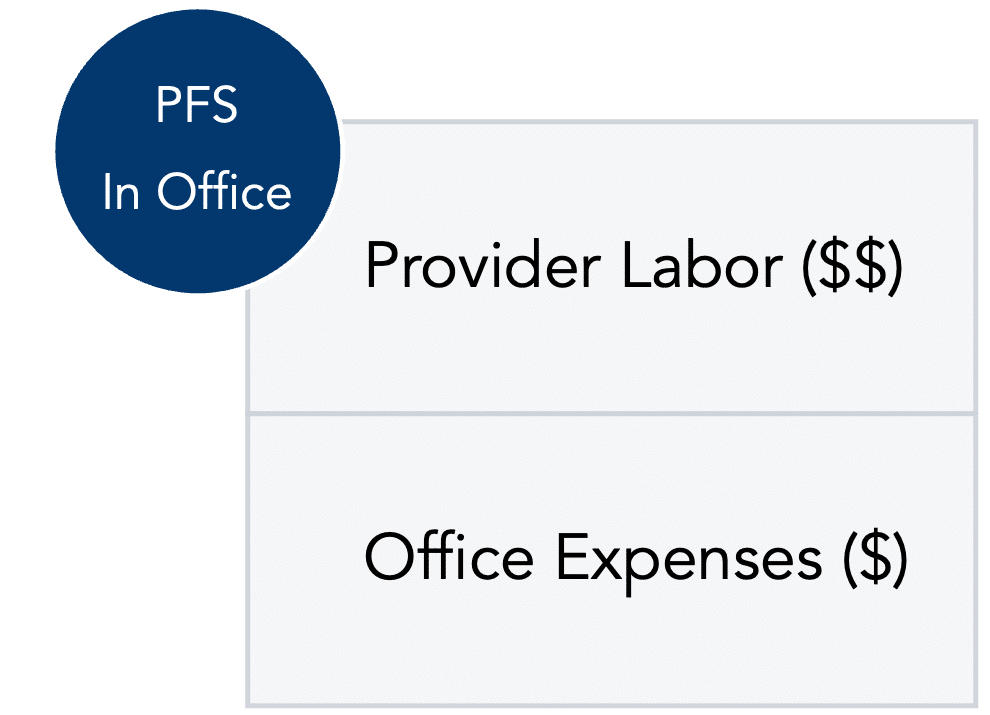

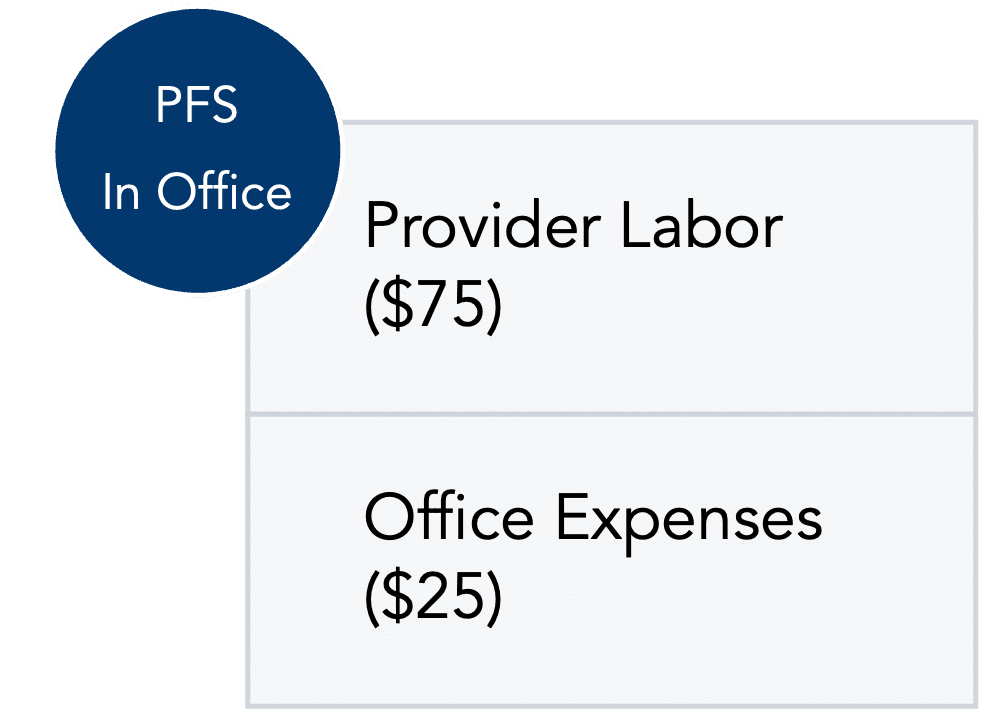

PFS In-Office Visits

When providers see patients in freestanding offices, they receive the provider rate plus reimbursement for office expenses.[vi]

For illustration, let’s assume the provider labor for a visit is $75 and the expected office expenses are $25.

The total for that visit is $100. The default Medicare cost-sharing is 20%, so a Medicare beneficiary would generally be expected to pay $20 for this office visit.

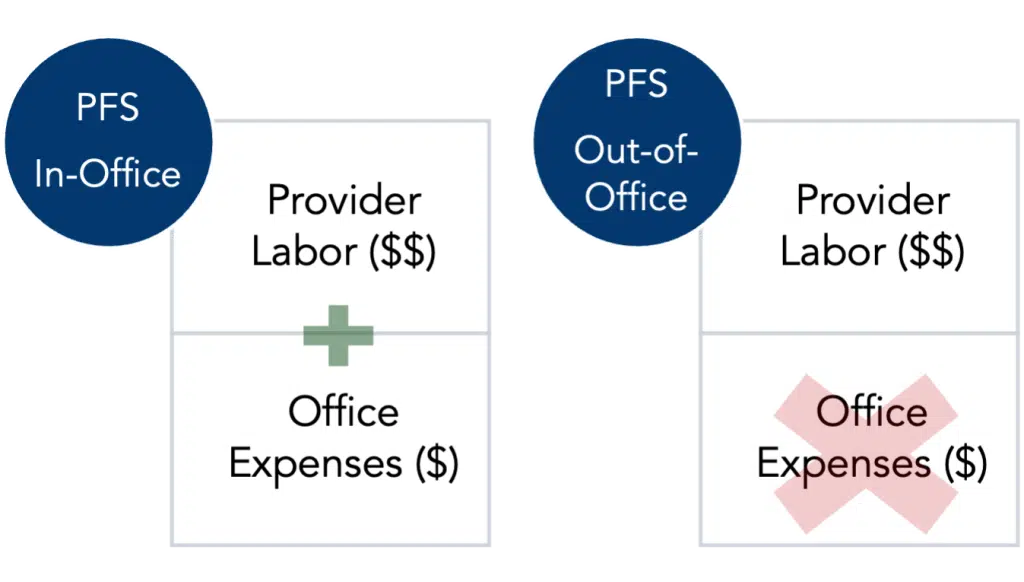

PFS Visits in Facilities

When providers see Medicare patients in facilities, Medicare still pays for their labor using the PFS. But the providers do not get Medicare payment for overhead office costs because the services are not in the office and are assumed not to increase expenses for the office.[vii] Instead, the provider gets the out-of-office PFS rate, also called the “facility rate,” and another payment system usually comes into play.

When the setting is a HOPD or an Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC), the rest of the rate is controlled by the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS).

The OPPS

The OPPS is the standard for how Medicare pays for services provided in HOPDs and ASCs.[viii] As with the PFS, CMS adjusts the OPPS each year to account for changes in expected costs for these departments, including overhead, supplies, and equipment. While these rates cover the same types of expenses as those the PFS covers, there is a key difference: Medicare assumes it is more expensive to perform medical services in hospitals (including HOPDs) and ASCs than in a freestanding provider’s office and sets its rates accordingly.[ix]

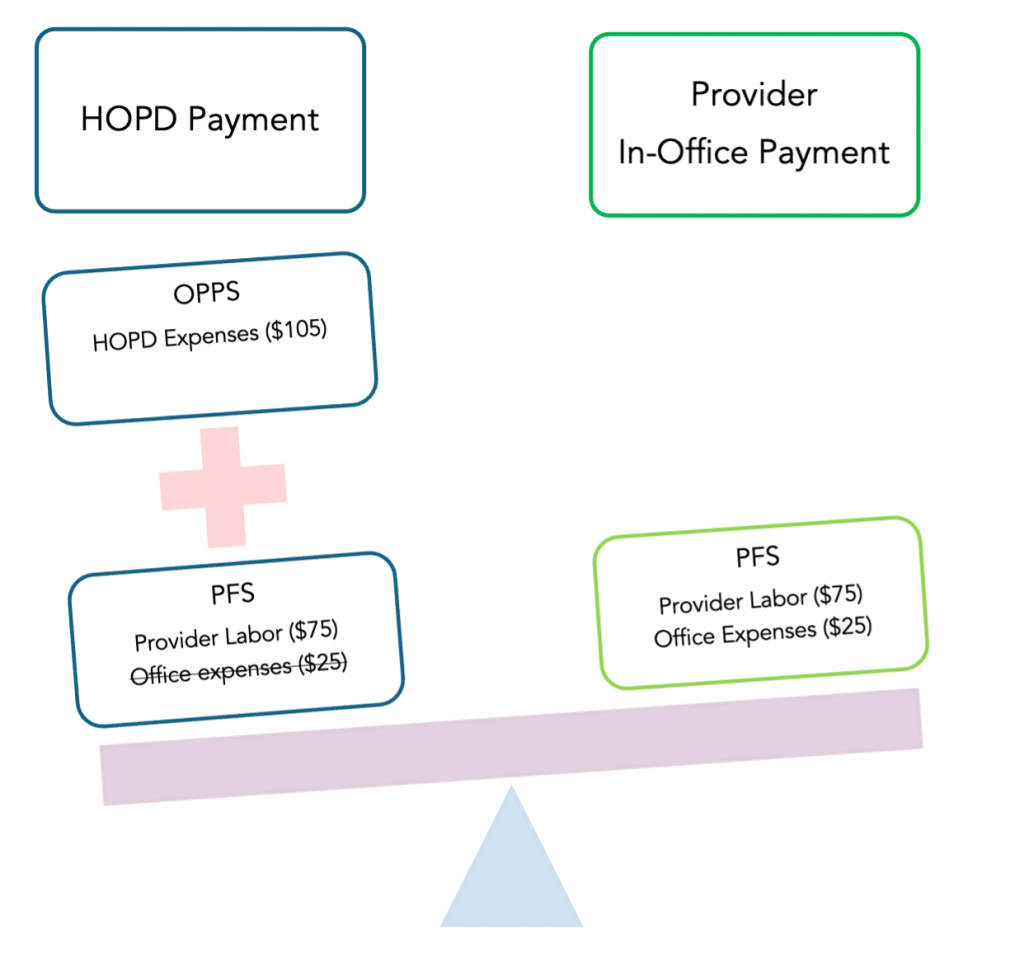

When providers work in facilities like HOPDs, they receive the PFS out-of-office rate, and the facility receives the higher OPPS rate. This means that even when the services and patient needs are otherwise the same,[x] care in a HOPD triggers a higher—even two or three times higher—total payment from Medicare than care in the same provider’s office.[xi]

For example, in 2023, HOPDs were reimbursed an average of $332.62 for chemotherapy infusion, 2.5 times more than the $132.16 for in-office providers.[xii] The spread in other cancer treatments can be even greater.[xiii]

As above, let’s assume that the provider labor for a visit is $75. But this time, the beneficiary is going to a HOPD for their visit. Instead of $25 for the provider’s office expenses, Medicare pays $105 for the HOPD’s expenses. This brings the total visit to $180 instead of $100 and hikes the beneficiary’s 20% share from $20 to $36.

What Is a Hospital Outpatient Department Anyway?

A HOPD is a part of a hospital system that provides care that does not require an overnight stay. Generally, outpatient services are less complex than inpatient services—those that require an overnight stay—and people can return home after the service or procedure.[xiv]

HOPDs can be “on-campus” or “off-campus.” An on-campus HOPD is one that is close to the rest of the hospital, often in the same or an adjacent building. Off-campus HOPDs are farther away from the main body of the hospital. Sometimes, these off-campus sites started as freestanding provider offices that a hospital system purchased and designated as an HOPD.[xv]

What About Ambulatory Surgical Centers?

ASCs provide outpatient surgical care. As with other outpatient services, ASC procedures do not require an overnight stay, so patients can go home the same day as their procedure.

Like HOPDs, ASC rates are set in the OPPS.[xvi] In general, these rates are lower than those of HOPDs but higher than the PFS in-office rate.[xvii] Because ASCs are generally less expensive for patients, they can often compete effectively against HOPDs for these outpatient procedures. Provider payment is equivalent between the two facility types; for both HOPDs and ASCs, providers are reimbursed at the PFS out-of-office rate.

Growth in HOPD Services

HOPD services have become more popular over the years, and this has significant ramifications for people with Medicare since most beneficiary spending is based on coinsurance that changes as rates change. From 2012 to 2022, Medicare and beneficiary spending on hospital outpatient services increased by 73%, an average of 5.6% per year.[xviii]

From January 2019 to January 2022, hospital employment of physicians increased by nearly 60,000, resulting in 52.1% of physicians working for hospitals and health systems rather than in independent practice, compared to 46.9% in 2019.[xix] More strikingly, by January 2022, hospitals and health systems owned 53.6% of physician practices, up from 38.8% in 2019.[xx]

These acquisitions have influenced provider behaviors, and Medicare beneficiaries receive more services in HOPDs than they used to.[xxi] Studies have found that independent providers and those that are vertically integrated with a hospital—meaning they are owned by the hospital or by another entity that owns both—have different referral and treatment patterns. Vertically integrated providers are more likely to refer patients to or treat patients in their hospital than independent providers are, eschewing both ASCs and keeping patients in-office at a higher rate.[xxii] In one study, providers who became vertically integrated after beginning to practice drifted away from ASC use, shifting procedures to HOPDs about 18% of the time in the four years after acquisition.[xxiii] The effect is more stark for providers who were never independently employed; vertically integrated providers were 65% less likely to use an ASC at all.[xxiv]

The drift toward HOPDs is not just for surgical procedures. One analysis showed that vertical integration both increased the raw number of five diagnostic imaging and five laboratory tests, and also shifted sites of care from nonhospital to hospital settings. Combined over a four-year period, the excess Medicare reimbursement from this shift was an average $6.38 per imaging test, adding up to $40.2 million, and $0.57 per laboratory test, adding up to $32.9 million.[xxv] This study highlights how the growing trend of vertical integration, combined with differences in Medicare payment between hospitals and nonhospital providers, leads to higher Medicare spending.

While providers themselves do not necessarily directly gain from changing care settings because of how the PFS and OPPS interact, the shift from offices to HOPDs increases Medicare’s payments. In the study above, a shift from in-office to HOPD settings triggered a 29% increase in outpatient reimbursement with no increase in the frequency of treatment.[xxvi] And since beneficiaries generally pay a percentage of Medicare’s expenses as coinsurance, such hikes raise beneficiary costs. MedPAC highlighted the example of office visits where a modest increase from 9.6% in HOPDs in 2012 to 13.1% in 2019 led to a jump in Medicare spending by $615 million and beneficiary costs by $150 million.[xxvii]

This increased reimbursement for HOPDs, as opposed to freestanding provider offices, has historically incentivized hospitals to buy up provider practices and call their former freestanding offices “HOPDs.” This allows hospitals to collect OPPS payments for services at those sites while baffling and enraging patients who receive surprise bills that reflect higher hospital-based prices for what looks like a standard freestanding office visit.[xxviii]

Discussion

One possible solution for this problem is for Medicare to adopt site-neutral payments. Under such a system, CMS would pay the same rate for the same service, regardless of where it is provided. MedPAC, an independent government agency that advises Congress about Medicare issues, estimated that inflated site-based payments increased beneficiary costs by nearly $1.7 billion and Medicare’s by $6.6 billion in 2019 alone.[xxix]

There are important limits to site neutrality. Higher-cost facilities are appropriate when services are more complex or when patients are more medically fragile. But the underlying premise of this approach appropriately recognizes that Medicare should not pay more without cause.

Policymakers have taken an interest in site-neutral payments,[xxx] but reforms have historically been limited.[xxxi] In the Balanced Budget Act of 2015, Congress took steps to align rates paid to some HOPDs—those located “off-campus” from the hospital—with the PFS. However, lawmakers made so many exceptions for so many facilities that the change affects less than 1% of hospital outpatient spending.[xxxii] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that ending these exemptions would save Medicare approximately $40 billion over 10 years.[xxxiii]

Other changes could have an even bigger effect. For instance, MedPAC has recommended paying HOPDs the lower PFS rate for services that can be safely delivered in an office setting, such as routine visits and imaging.[xxxiv] According to CBO, this would generate an additional $100 billion in savings.[xxxv]

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates site neutrality changes like those outlined above could save Medicare $141 billion over 10 years,[xxxvi] while others put the number slightly higher at $153 billion, including $94 billion in lower beneficiary costs.[xxxvii] And some take a broader view, accounting for potential savings beyond Medicare, since other payers—like commercial insurance—often follow Medicare’s lead and would also likely lower payments.[xxxviii]

Unequal and irrational payment affects Medicare spending and drives up costs for people with Medicare—through premiums and coinsurance for unnecessarily expensive care—and other taxpayers.[xxxix]

While higher rates for HOPDs may be appropriate in some instances, such as where the services or patient status increase risk or complexity, the current billing system does not allow for that nuance. Increased site neutrality for certain low complexity services would improve Medicare payment accuracy and generate significant savings while making vertical consolidation less attractive.

Endnotes

[i] Zachary Levinson, et al., “Five Things to Know About Medicare Site-Neutral Payment Reforms” (June 14, 2024), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/five-things-to-know-about-medicare-site-neutral-payment-reforms/.

[ii] Frederick Isasi, et al., “Gaming the System: How Hospitals Are Driving Up Health Care Costs by Abusing Site of Service” (June 2023), https://familiesusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Gaming-the-System-How-Hospitals-Are-Driving-Up-Health-Care-Costs-by-Abusing-Site-of-Service.pdf.

[iii] Zachary Levinson, et al., “Five Things to Know About Medicare Site-Neutral Payment Reforms” (June 14, 2024), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/five-things-to-know-about-medicare-site-neutral-payment-reforms/.

[iv] 88 Fed. Reg. 81540.

[v] Medicare Advantage plans can negotiate rates with providers. These rates can be higher or lower than the rates paid by Original Medicare.

[vi] This rate is the “non-facility” rate because the services are not provided in a facility.

[vii] This rate is the “facility” rate because the services are provided in a facility.

[viii] 88 Fed. Reg. 81540.

[ix] Frederick Isasi, et al., “Gaming the System: How Hospitals Are Driving Up Health Care Costs by Abusing Site of Service” (June 2023), https://familiesusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Gaming-the-System-How-Hospitals-Are-Driving-Up-Health-Care-Costs-by-Abusing-Site-of-Service.pdf.

[x] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Chapter 6: Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_Ch6_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_SEC.pdf.

[xi] See, e.g., Zack Cooper, et al., “Review of Expert and Academic Literature Assessing the Status and Impact of Site-Neutral Payment Policies in the Medicare Program” (October 30, 2023), https://tobin.yale.edu/sites/default/files/2023-10/Site-Neutral%20Payment%20Literature%20Review%2010302023.pdf; Jackson Hammond, “Site-neutral Payments” (May 4, 2023), https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/site-neutral-payments/; American Medical Association, “Payment variations across outpatient sites of service” (2023), https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/issue-brief-pay-variations-outpatient-sites.pdf; MedPAC, “Outpatient Hospital Services Payment System” (November 2021), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/medpac_payment_basics_21_opd_final_sec.pdf; and Loren Adler, “Testimony of Loren Adler, MS Associate Director and Fellow, USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy Economic Studies, Brookings Institution” (April 26, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2023-04-26-EC-Competition-Transparency-Testimony-Final.pdf.

[xii] American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, “Examining the Impact of Site Neutral Payment on Costs for Cancer Care” (October 19, 2023), https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/acs_can_site_neutral_issue_brief_-_final_10-19-23.pdf.[xiii] American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, “Examining the Impact of Site Neutral Payment on Costs for Cancer Care” (October 19, 2023), https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/acs_can_site_neutral_issue_brief_-_final_10-19-23.pdf.[xiv] Shanley Chien, “Ambulatory Surgery Center vs. Hospital Outpatient Department: How Are They Different and How Do You Choose?” (January 27, 2025), https://health.usnews.com/best-ascs/articles/what-is-an-ambulatory-surgery-center-asc.

[xv] Zachary Levinson, et al., “Five Things to Know About Medicare Site-Neutral Payment Reforms” (June 14, 2024), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/five-things-to-know-about-medicare-site-neutral-payment-reforms/.

[xvi] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “CY 2025 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Proposed Rule (CMS 1809-P)” (July 9, 2024), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cy-2025-medicare-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-system-and-ambulatory-surgical-center.

[xvii] David McMillan, et al., “HOPDs vs. ASC: Understanding Payment Differences” (May 19, 2019), https://www.hfma.org/operations-management/ambulatory-care/hopds-vs-asc-understanding-payment-differences/; Shanley Chien, “Ambulatory Surgery Center vs. Hospital Outpatient Department: How Are They Different and How Do You Choose?” (May 9, 2024), https://health.usnews.com/best-ascs/articles/what-is-an-ambulatory-surgery-center-asc.

[xviii] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program,” Chart 7-9 (July 2023), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/July2023_MedPAC_DataBook_SEC.pdf.

[xix] Avalere Health, “COVID-19’s Impact On Acquisitions of Physician Practices and Physician Employment 2019-2021” (April 2022) (https://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/PAI-Research/PAI%20Avalere%20Physician%20Employment%20Trends%20Study%202019-21%20Final.pdf.

[xx] Avalere Health, “COVID-19’s Impact On Acquisitions of Physician Practices and Physician Employment 2019-2021” (April 2022) (https://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/PAI-Research/PAI%20Avalere%20Physician%20Employment%20Trends%20Study%202019-21%20Final.pdf.

[xxi] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Chapter 6: Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_Ch6_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_SEC.pdf.

[xxii] Michael R. Richards, et al., “Treatment consolidation after vertical integration: Evidence from outpatient procedure markets” (July 6, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-1.html.

[xxiii] Michael R. Richards, et al., “Treatment consolidation after vertical integration: Evidence from outpatient procedure markets” (July 6, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-1.html.

[xxiv] Michael R. Richards, et al., “Treatment consolidation after vertical integration: Evidence from outpatient procedure markets” (July 6, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-1.html.

[xxv] Christopher M. Whaley, et al., “Higher Medicare Spending On Imaging And Lab Services After Primary Care Physician Group Vertical Integration” (February 13, 2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9924392/.

[xxvi] Michael R. Richards, et al., “Treatment consolidation after vertical integration: Evidence from outpatient procedure markets” (July 6, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-1.html.

[xxvii] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Chapter 6: Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_Ch6_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_SEC.pdf.

[xxviii] Anna Claire Vollers, “You’ve covered your copayment; now brace yourself for the ‘facility fee’: States are going after the surprise charges tacked on by hospitals that own outpatient centers” (April 25, 2024), https://stateline.org/2024/04/25/youve-covered-your-copayment-now-brace-yourself-for-the-facility-fee/.

[xxix] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Chapter 6: Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_Ch6_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_SEC.pdf.

[xxx] Pub. L No. 114-74.

[xxxi] Zack Cooper, et al., “Review of Expert and Academic Literature Assessing the Status and Impact of Site-Neutral Payment Policies in the Medicare Program” (October 30, 2023), https://tobin.yale.edu/sites/default/files/2023-10/Site-Neutral%20Payment%20Literature%20Review%2010302023.pdf; Government Accountability Office, “Medicare: Increasing Hospital-Physician Consolidation Highlights Need for Payment Reform” (December 18, 2015), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-16-189.

[xxxii] Loren Adler, “Testimony of Loren Adler, MS Associate Director and Fellow, USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy Economic Studies, Brookings Institution” (April 26, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2023-04-26-EC-Competition-Transparency-Testimony-Final.pdf; . Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_v4_SEC.pdf.

[xxxiii] Congressional Budget Office, “Proposals Affecting Medicare—CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Fiscal Year 2021 Budget” (March 2020), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2020-03/56245-2020-03-medicare.pdf.

[xxxiv] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Chapter 6: Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings” (June 2022), https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_Ch6_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_SEC.pdf.

[xxxv] Congressional Budget Office, “Proposals Affecting Medicare—CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Fiscal Year 2021 Budget” (March 2020), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2020-03/56245-2020-03-medicare.pdf.

[xxxvi] Government Accountability Office, “2023 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Billions of Dollars in Financial Benefits—Open Matters and Recommendations with Potential for Financial Benefits” (June 14, 2023), https://files.gao.gov/reports/106089/index.html#finding3.

[xxxvii] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget Health Savers Initiative, “Equalizing Medicare Payments Regardless of Site-of-Care” (February 23, 2021), https://www.crfb.org/papers/equalizing-medicare-payments-regardless-site-care.

[xxxviii] Zack Cooper, et al., “Review of Expert and Academic Literature Assessing the Status and Impact of Site-Neutral Payment Policies in the Medicare Program” (October 30, 2023), https://tobin.yale.edu/sites/default/files/2023-10/Site-Neutral%20Payment%20Literature%20Review%2010302023.pdf.

[xxxix] Board of Medicare Trustees, “2024 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund,” Appendix E (May 6, 2023), https://www.cms.gov/oact/tr/2024.

Recent Resources

Any changes to the Medicare program must aim for healthier people, better care, and smarter spending—not paying more for less. As policymakers debate the future of health care, we will provide our insights here.

Thinking ahead to Medicare's future, it’s important to modernize benefits and pursue changes that improve how people with Medicare navigate their coverage on a daily basis. Here are our evolving 30 policy goals for Medicare’s future.

You can help protect and strengthen Medicare by taking action on the important issues we are following, subscribe to newsletter alerts, or follow along on social media. Any way you choose to get involved is a contribution that we appreciate greatly.